Serum Institute's Adar Poonawalla is more than just a businessman

Serum Institute of India CEO Adar Poonawalla's luxurious abode in Pune is adorned with rare paintings

and boasts of stunning architecture

Images: Vikas Khot

You get a glimpse of the good life even before you enter the Poonawallas’ Pune home. The architecture of the house, named Adar Abad, is distinctly European. Six large columns support the elevated front lobby which has striking orange Italian marble flooring. On one side of the lobby stands a 40-year-old single engine Cessna aircraft. On the other side is ‘Lil’ Cyrus’s Stable’ which houses a Shetland pony (a breed of horses that are short but sturdy). Inside, the living room is large with a high ceiling and a dome that allows sunlight to flood in. What immediately catches your eye are the frescoes in the ceiling; they are inspired by one of the great masters of Italian Renaissance, Michelangelo, and his work at the Sistine Chapel, the official residence of the Pope in Vatican City. Ming vases, riding trophies and other figurines dominate the room and paintings by Vincent van Gogh (Water Mill at Opwetten), Renoir (who celebrated the feminine), AJ Munnings (of horses, what else) and Marc Chagall (from his work on flower vases) populate the walls.

A bright spot on one of the walls draws your attention—a closer look reveals that the shine is provided by 20 silver plates with Pablo Picasso’s paintings imprinted on them. “This is my favourite,” says Adar Poonawalla, the 35-year-old CEO of Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest maker of vaccines (in terms of dosage). “Imprinted are some classics, including Visage Larvae, Centaure, Visage de femme, Un Poison and Le Dormeur.”

Adar has just joined us, having walked down one of the two spiral staircases that connect the living room to the upper floors. The living room can accommodate two big chandeliers and dwarf a large piano. “We bought the chandeliers over the years from maharajas who were stretched for cash,” says Adar, the only son of Cyrus Poonawalla, the founder of the vaccine maker, who is ranked number 10 on the 2016 Forbes India Rich List with a wealth of $8.6 billion. “Tom Ford, Huntsman and Brioni are my favourite brands when it comes to what I wear,” says Adar, nattily dressed in a Savile Row suit, a Dolce & Gabbana shirt and a Tom Ford tie, as he settles down for a chat with Forbes India. We have, by then, walked across to the sizeable dining room sparkling with silver cutlery.

As we converse, it becomes clear that Adar has not only imbibed his father’s business acumen—Serum Institute’s revenues, he says, have grown at a compounded annual growth rate of 32 percent and profits by 30.5 percent since he took over as CEO in 2011—and taste for the fine things in life, but he has also done one better by exercising social responsibility with the Adar Poonawalla Clean City Movement in Pune, as well as other initiatives in the areas of drinking water and sanitation.

Being the only child to wealthy parents did not translate into an easy childhood for Adar. “I am not a mollycoddled child,” he says. He was sent to a boarding school, St Edmund’s School, Canterbury, in England, when he was nine. “In spite of him being my only son, I threw him into the deep end. That has shaped him well as a person and as an entrepreneur,” says his father, the 75-year-old Poonawalla who set up Serum Institute 50 years ago. “Today, he can stand on his own feet and face challenges with an independent mindset.” And Adar has proved this more than once.

Though Adar still enjoys material things, the rate at which he buys them has slowed down significantly

The Businessman

Adar joined Serum Institute in 2001, fresh out of college, after graduating in business management from University of Westminster, England. He was just 20 then. “I had no official designation. My job was to just shadow my father, observe and learn. He wanted it that way,” explains Adar who, unlike many billionaire kids, does not have a postgraduate degree from a fancy college. “My father feared that I would get distracted, get used to the nice life abroad and not return to India at all. This has happened in many second-generation business families. So he asked me to come back after graduation.”

Adar has no regrets. After all, it gave him the opportunity to learn the business hands-on. “No classroom can give you the sort of exposure that you get by dealing with failure and success. All the theories in the world won’t help,” he says.

In 2005-06, Adar joined the company’s board of directors as executive director. At that time, Serum Institute was supplying vaccines to about 35 countries apart from India. The domestic market was difficult as the governments (both state and central) were not investing enough in vaccines and getting payments from government agencies was a time-consuming process. To circumvent this situation, Adar decided to expand their business geographically. He got his products validated globally and began supplying to the World Health Organization (WHO) and other aid agencies across many needy countries. Today, Serum Institute supplies vaccines to 145 countries and almost 80 percent of the company’s revenues come from outside India. This success established Adar’s management skills and credibility within the organisation and outside. He was made the CEO in 2011 and his father took a step back from day-to-day operations.

Adar has since broadened Serum Institute’s scope of business further. Traditionally, the closely-held unlisted company has been strong in the DPT (diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus) and MMR (measles and mumps) families of vaccines. Adar began to take the company into newer segments. The launch of the oral polio vaccine in 2013, for instance, was his other big success and he achieved it despite plenty of scepticism from people around him, including his father. “Polio will be eradicated very soon. What is the point in developing an oral version of it now, my father asked,” recalls Adar. “I went against the grain and rejigged the manufacturing facility to produce it.” Today, the vaccine generates as much as $70 million in revenue for Serum Institute. “It is a big hit and delivers 10 percent of our annual profits,” says Adar. Serum Institute has also launched vaccines for bladder cancer and influenza.

In 2012, Adar led Serum Institute to its first overseas acquisition when it took over The Netherlands-based Bilthoven Biologicals for Rs 550 crore. The deal not only gave Serum Institute the technology to produce injectible polio vaccines (which it launched soon after) but also a manufacturing base that acted as a strategic beachhead for Europe and the US.

According to Serum Institute, 65 percent of the children in the world receive at least one vaccine produced by it. The significance of this data point gets magnified when one considers that the vaccines it sells are at a far lower price than its competitors such as GSK, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis and LG Life Sciences. “All our vaccines are at half the price sold by big players. Our philosophy is that prevention is better than cure at affordable prices,” says Adar. “Poor countries cannot afford the vaccines but they have the right to health.”

Adar, seen here with father Cyrus, apprises PM Narendra Modi of the Adar Poonawalla Clean City Movement

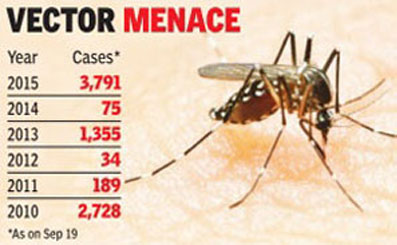

Adar is also building a very strong product pipeline. In 2017, Serum Institute will launch rotavaccine, or rotavirus vaccine, which prevents diarrhoea among babies and small children. This will be followed by TDaP (adult tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis), dengue, HPV (prevents cervical cancer) and pneumococcal (prevents pneumonia) vaccines. While these will go a long way in reducing large-scale mortality among babies, children and women, it is critical for Serum Institute’s future profitability as well. “The vaccine industry works with a herd mentality. If a company launches a particular vaccine, all others follow suit. So you have good profits for four to five years after which products from competition flood in and revenues/profits disappear,” he explains. “I need products to come in by 2017-18 or else my growth will suffer.”

Serum Institute is investing Rs 2,000 crore over the next three years to increase production capacity (from 1 billion dosages now to 1.5 billion by 2020). “We have ploughed back almost 80 percent of our profits into the business to build our quality, technology and capacity,” says Adar. The new facility will also help Serum Institute foray into the US market. “We have always dreamt of entering the US market. Real revenue lies there as the vaccines are sold at prices which are 15 times that of India,” he says. “But it costs $60 million to launch a product in the US and Europe.” However, the company feels that it now has the financial clout and the required infrastructure to enter those markets.

Adar’s vision and leadership is acknowledged by his business associates. “Serum Institute is an important partner for us,” says Harish Iyer, senior advisor, Scientific Programme, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The two organisations have been working together to fight debilitating diseases around the world. “When I was CEO of Shantha Biotechnics [a vaccine maker] between 2011 and 2015, I always admired Serum Institute for its technical capability, solid understanding of the issues involved and product development capabilities,” Iyer adds.

Serum Institute developed a meningitis vaccine in collaboration with Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and this, according to Iyer, helped control the disease in Africa. “Adar understands the world of public health and what type of products work. He believes in his people and has the right talent around him,” says Iyer. “A lot of responsibility rests on his shoulder and he is forced to take challenging decisions often.”

He seems to be dealing with his responsibilities to his father’s satisfaction. “It is a pleasure to see my boy shaping up,” says Poonawalla senior. “Adar is working very hard compared to most of his peers. He is ready to learn from his mistakes, which is a very important quality to develop.”

Adar, on his part, thanks his father for giving him full freedom. “I was just 30 when I became the CEO. The freedom he gave allowed me to blossom and grow. Only when you are completely unleashed, can you reach your full potential,” he says.

Adar has also been aided by his father’s tutelage, through which he has learnt some valuable lessons in management. “He had an eye for detail and I have imbibed it from him. Knowing everything that happens in the company is the key,” he says. Ask him if that is not micro-management, and he responds promptly: “Lots of people criticise us for micro-managing. But if you look at history, many companies have suffered because the promoters have taken their eyes off the business. We do not let grass grow under our feet.”

He wants Serum Institute’s revenue to touch Rs 10,000 crore by 2020 from around Rs 4,200 crore now. “We may be the largest manufacturers of vaccines in terms of dosage but in terms of revenues, ours are a tenth of our next competitor Sanofi,” Adar says. Also, more acquisitions could happen. “I can leverage as much as a billion dollars on my balance sheet. I am also willing to dilute my stake in case the acquiring company is very strategic in terms of technology, capacity, market share and products,” he adds.

What he is dead against is an IPO. “I do not want to lose independence and start reporting results quarter after quarter. Our decisions will never be the same then,” he says.

After Hours

His plans seem to be falling in place, allowing Adar a moment or two of calm. Those moments, he says, he uses well: Either holidaying by chartering a yacht and sailing in the south of France, or renting a villa in Italy or France and spending time there. “I have been there [to those parts] some 50 times so far,” he says. His Gulfstream G550 aircraft is his transportation of choice. “With a 13-hour range, it can take me to anywhere in the world with a single halt,” he says. The plane can also come in handy when he craves continental food and in case he wants to fly in Michelin star chefs to cook for his friends and him.

He loves movies too and catches up on them in his private theatre. “Gladiator is my all-time favourite.”

His other passion is speed. Tucked away in the basement of his house are three simulators: There is a Boeing 737 flight simulator apart from Formula 1 and fighter jet simulators. And, in his garage, he has a 20-plus strong fleet of cars. This includes the choicest of vehicles: Rolls-Royce, Ferrari, Bentley, Lamborghini, Chevy Corvette and Hummer (electric vehicle).

“I take them out over the weekends mostly late in the night. Only then can I drive them,” he says.

A collector of watches, especially tourbillons, his stash includes Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet and Roger Dubuis. However, he points out, “I haven’t worn a watch for the last two years.” What has also changed: “I still enjoy material things but the rate at which I buy them has slowed down significantly.”

The Mercedes-Benz S-Class that Adar got modified to look like a Batmobile for his son Cyrus's 6th birthday

This is a change that Adar began to feel when he turned 30. His mother Villoo Poonawalla passed away in 2010 and it was only after her death that he learnt about the charity work she was discreetly engaged in. That triggered an interest in him for doing good for others. “The smile I see on the faces of beneficiaries is a lot more satisfying than buying cars,” he says. He set up the Villoo Poonawalla Charitable Foundation in 2013 in the memory of his mother and pledged Rs 100 crore of his personal money to initiatives involving clean city, water management and sanitation. His wife Natasha helps him in this endeavour.

It was in January this year that he started the Clean City Movement to rid Pune of garbage. “I am proud to be an Indian but when foreigners see filth on the streets, my pride gets damaged,” he says. In fact, not only did he put in the money, he also chose to execute the project himself. In this, he was inspired by Bill Gates with whom he has worked closely and who he sees as his mentor.

“He spends a good amount of his personal time for doing good and it helps. It is an inspiration,” says Adar, who was included in Forbes Asia’s Heroes of Philanthropy 2016 for his Pune initiative.

The Clean City project now has 111 sophisticated vehicles, many of which are imported from Europe to clear the garbage. Over 150 people are employed. “Our mission is to cover the entire city by 2017,” says Krishnan Komandur, CEO, Adar Poonawalla Clean City Movement. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, during a recent visit to Pune, met Adar to apprise himself of the initiative.

The Poonawalla foundation is also building toilets in Mumbai and Pune, as well as setting up water treatment plants to supply clean drinking water. “I plan to give 10 million litres of water per day and this will benefit 12 million households,” he says. “I like to live by the philosophy: Live well and help others live well.”

The most critical part of his good life, though, is the time with his children: Cyrus, 7, and Darius, who turns one in December. In fact, his gift for Cyrus’s 6th birthday surprised not only his son but the city of Pune.

Adar had modified a Mercedes-Benz S-Class—this was done in China and took six months to accomplish—to look like a Batmobile and took his son out for a spin on his birthday. The social media in Pune was agog with curiosity about the mysterious vehicle before its identity was revealed. “My son loved it and if you ask me, it is the most precious possession I have today.”

Source: Forbes India